How Did The Arts Change As A Result Of The Enlightenment

vi The Enlightenment on art, genius and the sublime

Enlightenment ideas on art and the creative process were deeply influenced by the contemporary veneration for reason, empiricism and the classics. The business organisation of the creative person was conceived of equally the imitation of nature, and as far as loftier art was concerned, this process of fake should be informed by an intelligent grasp of the processes used to produce classical fine art. The ancients and their art were seen every bit models in the judicious choice of the about cute elements observed in nature, creating forms of ideal or 'beautiful' nature that were derived from a distillation of the very best and a filtering out of physical flaws. The leading art critic Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–68) held up Greek statuary for imitation as the apotheosis of perfection. Transmitted to the eighteenth century via a robust Renaissance artistic tradition based on the antique, Enlightenment Neoclassicism in its broadest sense attempted non only direct borrowings from the antique (the imitation of architectural motifs, the use of classical drapes to clothe figures, idealised treatment of the human figure based on antique sculpture, reference to sculptural poses), but also an emulation of the order, unity, proportion and harmony felt to underpin all classical art. The principles of classical composition were based on the notion of a articulate focus on a central motif (a hero, martyr or saint); one thousand, unifying (as opposed to sparkling, dappled or disjointed) furnishings of light and shade that wouldn't distract the eye to the detriment of mental focus on an elevating subject field; noble simplicity, balance and symmetry (see Figure vii). Y'all volition find in the art of Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) the expression of a particularly pure form of classical limerick.

Effigy 7 Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family unit in Egypt, 1655–vii, 105 x 145.5 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, Saint petersburg.The principles of classical composition demonstrated in this painting – residuum, symmetry, wide, unified light effects and a prominent, hierarchical positioning of the main figures-influenced generations of eighteenth-century painters. Poussin was greatly influenced by antique friezes and bronze

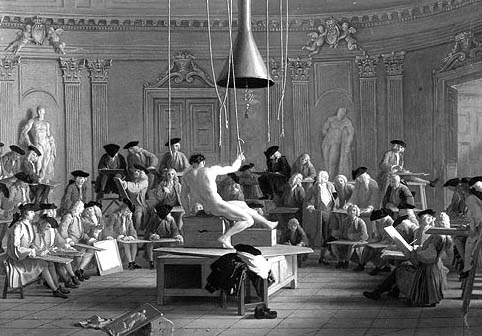

Every bit the century progressed, the dangers of servile imitation, or a formulaic approach to art, were increasingly recognised as the claims for more 'natural' art were asserted. A meaning body of opinion developed that was disquisitional of artists who simply imitated the art of the past in a way that degenerated into bamboozlement and mannerism. In the 1760s Diderot, who also wrote as an art critic, was among those who insisted that artists should pay more respect to nature. Study of idealised antique statuary and the principles of anatomy and proportion that had informed it remained of import to artists, but it was stressed increasingly that respect for these must not exclude or diminish kickoff-hand observation of the man trunk. Life drawing classes at the academies of art allowed male artists to study the nude, but the human models were normally posed in highly artificial means that complied with the conventions of antique sculpture; their poses and the positions of their limbs were fixed in the cartoon studio by a complex organization of ropes, pulleys and blocks (see Figure viii). Theorists called increasingly for less bogus poses and methods of observation.

Figure 8 Michel-Ange Houasse, The Cartoon Academy, c.1725, 61 x 72.five cm, oil on sail, Purple Palace, Madrid. Photo: © Patrimonio Nacional

This growing quest for the 'natural' extended to changing views on the condition of unlike genres or subjects in art. While loftier fine art, inspired past classical or religious subjects, retained its position at the top of the hierarchies perpetuated by the academies of Europe, there was a growing appreciation of the lower genres of landscape, however life and scenes of everyday life, which required more than straight observation of a more natural reality. In landscape art, as you volition meet, the idealised classical landscapes of the seventeenth-century French artist Claude Lorrain (1600–82) remained extremely influential. But there was also an increasing trend to identify more emphasis on directly observed sketches of the mural that, while notwithstanding beautifying nature, immune for false of a greater variety of natural effects. Enlightenment artists and critics were emboldened to demand greater naturalism or realism in art, in both style and subject matter, every bit a outcome of the popularity of Dutch and Flemish paintings, which had generated a northern tradition increasingly seen as a real alternative to the classical. In England William Gilpin and other artists and writers interested in what they called the 'picturesque' advocated travel as a means of viewing real landscapes and directly observed sketches as office of the process of producing views 'fit for a picture'. The quest for greater naturalism was seen in France equally an antidote to the early eighteenth-century excesses of the Rococo, a specific adaptation or 'debasement' of the one thousand classical style characterised past serpentine curves and asymmetric forms applied mainly to portraiture and to erotic and playful mythological subjects (see Figure 9). In the second half of the eighteenth century, a greater respect for nature was seen equally a moral solution to the luxury and corruption of the Rococo's aristocratic patrons.

Figure ix François Boucher, The Triumph of Venus, 1740, oil on canvas, 130 ten 162 cm, National Museum of Fine Arts, Stockholm. Photo: National Museum of Fine Arts.Boucher's frivolous and erotic Rococo manner and treatment of mythological subjects exerted a large influence on mid-eighteenth-century gustation. Associated with aristocratic decadence, they led to calls later in the century for art that was both more than natural and more moral

Given the accent on imitation, it is peradventure unsurprising that the Enlightenment concept of the imagination was essentially that of producing new variations on old themes. The imagination was held to combine impressions observed in nature and previous art, but was generally non understood or required to include whatever great flights of fancy. The pleasance of fine art lay in the recognition of the familiar reprocessed in ways adapted to modern times. While the Encyclopédie commodity on 'Genius', written by Jean Francois de Saint-Lambert, defined genius as consisting of boggling powers of mind, intuition and inspiration transcending mere intelligence, most Enlightenment commentators on artful matters saw such qualities as appropriate to a specific stage of the creative process (the initial moment of inspiration, the preliminary sketch) rather than every bit qualities that should dominate or overwhelm. Genius was a quality of mind to be welcomed, merely the creative process must also involve reflection, written report and observation.

Indeed, many Enlightenment thinkers shared the conviction that good art was largely, though not exclusively, the product of compliance with well-established rules derived from the classics and empirical reason. As Voltaire observed in 1753, 'I value poetry but insofar as information technology is the ornament of reason' (quoted in Furst, 1969, p. 19). Voltaire's aesthetics, similar those of most French writers of the eighteenth century, were based on the neoclassical canons of literature laid downwardly in the reign of Louis XIV past such critics as Nicolas Boileau in his Art of Verse (1674). Then while Voltaire was a pioneer in introducing Shakespeare to the European public, he did so with profound reservations and, as it were, holding his olfactory organ, arguing that Shakespeare'southward plays included 'gold nuggets in a dung-heap'. He presented Shakespeare every bit a unique genius who succeeded despite such pitiful violations of the neoclassical rules every bit mixing comic and tragic elements in the same play. Voltaire was in good company in defending the accepted literary canons and explaining 'genius' as the exception that proved the dominion. Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–92), President of the Royal Academy in London, adopted the same view in relation to art:

Could we teach taste or genius by rules, they would no longer be gustation and genius. Simply though there neither are, nor tin be, any precise invariable rules for the practice, or the acquisition, of these great qualities, yet we may truly say that they always operate in proportion to our attention in observing the works of nature, to our skill in selecting, and to our intendance in digesting, methodising, and comparing our observations. At that place are many beauties in our art, that seem, at first, to prevarication without [exterior] the reach of precept, and withal may hands be reduced to practical principles.

(Reynolds, 1975, p. 44)

The artist, in other words, should non let his imagination run away with him. Hume, as well, warned of this danger:

The imagination of human is naturally sublime, delighted with any is remote and extraordinary, and running without command into the well-nigh distant parts of infinite and time in order to avoid the objects which custom has rendered also familiar to information technology.

(Quoted in Hampson, 1968, p. 158)

The deeper irony for today's reader is that it was precisely this unconstrained escapism into long ago and far away, the 'remote and boggling', that was to obsess and characterise the Romantics.

Summary betoken: Enlightenment ideas on art and the creative person were dominated by reason, moderation, classicism and control. However, there was recognition of the elusive quality of original 'genius'.

If most artful ideas of the Enlightenment emphasised reason and experience, and classified 'genius' as something outside the rules, in that location was ane further concept mentioned by Hume, 'the sublime', that seemed to strain Enlightenment rationality to its limits. Theorised past Edmund Burke in his Philosophical Enquiry, a sublime aesthetic experience was one that inspired awe and terror in the spectator or reader. The sublime was something literally overwhelming, either because of its enormity (a high mountain, a deep chasm, a blinding light), its infinity (the spiritual or timeless) or its obscurity (a deject-capped mountain, a floating mist, night, intense darkness) – all, significantly, the contrary of the precise, measured, penetrating 'light' of the Enlightenment. When faced with the sublime, the viewer, listener or reader felt a kind of paralysis of the will and of the powers of agreement and imagination. At the same fourth dimension, as an artful feel (grounded in art rather than reality) the sublime immune for the thrill of danger without its real consequences. Immensely popular in this context across Europe were the 'works' of Ossian, ostensibly a poetic cycle past a Gaelic bard of the third century CE, but in fact the invention of James MacPherson (1736–96), who published his prose 'translations' in 1760. Napoleon was among the many devotees of Ossian, equally much moved past the tales of legendary heroes in a wild, rugged and primitive northern setting as by Homer'southward more than familiar Greeks and Trojans. This kind of exalted experience was increasingly sought in art and by the late Enlightenment was a dominant artful mode:

It is night. I am alone, forlorn on the hill of storms. The wind is heard in the mountain. The torrent pours down the rock. No hut receives me from the rain, forlorn on the hill of winds. Rise o moon from behind the clouds. Stars of the night, arise!

(MacPherson, Colma's lament from Ossian, quoted in Barzun, 2000, p. 409)

In Mozart's Don Giovanni the sublime emerges in the infernal forces that swallow the chief grapheme at the finish of the opera, and perhaps in the sublime courage of the man who defies them. The epitome of Prometheus, the demi-god punished for his defiance of the male monarch of the gods, began to haunt the poetic imagination when Goethe (1749–1832) devoted to it a dramatic fragment and ode (1773). For the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, it was the possession of a non-fabric soul that allowed people to seize the infinity of the sublime. This sensation of phenomena straining or exceeding the limits of human understanding was later to class the ground of a fully-fledged Romantic aesthetic.

Summary bespeak: in the Enlightenment the theorisation and popularisation of the sublime began to undermine the eighteenth century's otherwise articulate accent on the knowable, the rational and controllable.

Source: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history-art/the-enlightenment/content-section-6

Posted by: tigerdurn1955.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did The Arts Change As A Result Of The Enlightenment"

Post a Comment